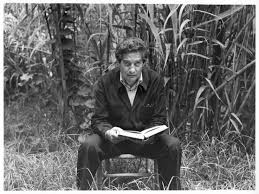

In allusion to Hanuman – a god belonging to Hindu mythology regularly present in the classic Ramayana – Octavio Paz presents us, in his work El Mono Gramático , with what is simultaneously a free revision of this and other Indian classics.

Paz demonstrates – as he did in his famous debate with Raimon Panikkar – a comfortable, sober and detailed mastery of the ancient Indian texts. But at the same time – without making explicit reference – he brings us closer, in some of the reflections that pepper the 29 chapters of this singular work – not ascribed to any other similar work by the author – to the first glimpsers of the limits of the language of the philosophical and literary tradition of the West. From the prophetic intuitions of Nietzsche to the formal and detailed insights of Wittgenstein, via the literary ironies of Voltaire in his Candide, epitomised by the late Professor Pangloss:“He who is all language“.

Paz demonstrates – as he did in his famous debate with Raimon Panikkar – a comfortable, sober and detailed mastery of the ancient Indian texts. But at the same time – without making explicit reference – he brings us closer, in some of the reflections that pepper the 29 chapters of this singular work – not ascribed to any other similar work by the author – to the first glimpsers of the limits of the language of the philosophical and literary tradition of the West. From the prophetic intuitions of Nietzsche to the formal and detailed insights of Wittgenstein, via the literary ironies of Voltaire in his Candide, epitomised by the late Professor Pangloss:“He who is all language“.

Hanuman, able to leap from India to Ceylon or to carry the Himalayas on his back, is also (or precisely) a grammarian.

Who else but a grammarian could face challenges of such magnitude? Who but someone capable of doing the most unimaginable juggling with words, the fundamental artifice – and artifice – with which we build the world?

And it is precisely in Hanuman’s grammatical facet where Paz lets us glimpse what the Orientals seem to have glimpsed for millennia (“Neti, neti“, the Buddha used to say when some scholar or some individual more imprisoned by language than usual approached him with dialectical questions) healthy double thread as an instrument for making “reality” intelligible. Allowing us the expression of the tiny part of knowledge (Do we know it?) to which we have access, it makes it impossible for us, by its very nature, to have precise knowledge beyond the limits that configure its architecture.

Now, are these architectures at the same time enabling and limiting? Is the grammar of Latin languages extrapolate to that of Germanic languages, and even these to some more exotic languages with a higher, more precise and rigorous presumption of accuracy and referentiality, such as Hebrew or Sanskrit itself? Perhaps one would have to be a scholar in the various Primarii Lapidis of each of these edifices of syntax, lexicon and various morphologies to venture hypotheses. And even then, perhaps only Hanuman knows his answer (which is no answer).

Could it be possible that language, with which we so gravely clothe identities and illusions (realities?), is nothing but a divertimento of the gods, or even more so, a simple child’s game?

☝🏻 Probably Gianni Rodari, author of “Grammar of Fantasy: An Introduction to the Art of Storytelling” would find it ridiculous to even ask the question.

In this sense, Paz questions us:“The relationship between rhetoric and morality is disturbing: the ease with which language is twisted is disturbing, and it is no less disturbing that our spirit so meekly accepts these perverse games. And he warns us: “We should subject language to a regime of bread and water, if we do not want it to be corrupted and to corrupt us. (The bad thing is that regime-of-bread-and-water is a figurative expression as is the corruption-of-language-and-its-contagions).

This suspicion, a peculiar intuition, is certainly not new in the West either. The sophist Gorgias already declared his famous theses (Nothing exists: If something existed, it would be unknowable; If it were knowable, it would be incommunicable) and the trilemma of Agrippa or Münchhausen paved the way on the cognitive side (reducing the linguistic faculty to three .

Likewise, Kurt Gödel’s incompleteness theorems, of unquestionable topicality, seem to support this direction. Also Bertrand Russell, who in his almost mystical account “The Metaphysician’s Nightmare” denounces the demonic realm (personified in the word “no”) as a banal, flawed linguistic habit. And continuing with mysticism, this one declared, an inquisitive Krishnamurti resounds: “Tell the child the name of the bird, he will never see it again“. And of course, the omnipresent Wittgenstein, who seems to whisper sporadically between the pages of this work his popular closing of the Tractatus: “What cannot be spoken of, it is better to remain silent“. But Paz (who knows if it is because of his poetic facet) is not paralysed by formalism, and instead of keeping silent, he uses language itself to confront language: “Even the simplest sentences must be unravelled to find out what they contain and what they are made of, why they are made? Unweave the verbal fabric: reality will appear“.

A metalinguistics of suspicion, which could well be a slave to itself.

For this reason, a question is read – as enigmatic as the very tool used to articulate it – recurrently among the symbols printed on its pages (still awaiting an answer from the first vestiges of civilisation to the present day):

📌 What is this Mystery called Language?

📎 Gallifa, G. [Guillem]. (2024, 20 November). Octavio Paz and the grammatical simiesque. PsicoPop. https://www.psicopop.top/en/octavio-paz-and-the-grammatical-simiesque/

📖 References: